Human Origins : Our Shared History to Your Story

The questions of who we are and where we come from have been asked for throughout our history. Once we explained our origins with mythology and folklore but now we utilize modern science to answer them. Genetics help us tell the story of our origins from the beginning, through the formation of the human gene pools and to the last 2000 years of history. The test results you have just received, along with the following information, will help you understand your personal story, from the shared history of all humans to your unique family story. Read More

GENE POOL PERCENTAGES

TOP 3 GENE POOLS

#1 Bantu Africa and the Niger-Congo Areas 33.2%

#2 West Africa 18.9%

#3 Madagascar 14.9%

GENE POOL REGIONS

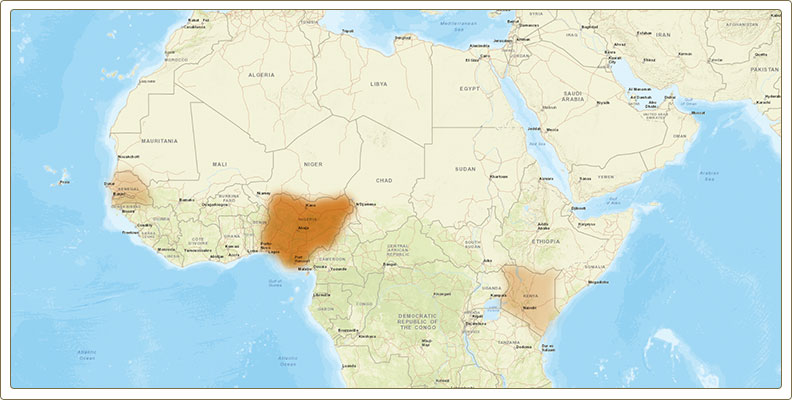

/ / / #1 Bantu Africa and the Niger-Congo Areas

The Bantu people currently include around 85 million speakers of around

Bantu Africa and the Niger-Congo Areas Story

Archaeological evidence suggests that the original Bantu-speaking homeland is genetically centered in Nigeria, West Africa. This area was home to ancient-human ancestors up to 2 million years ago. These ancient humans are associated with a tool culture known as the Acheulian,1 which is found in many other surrounding regions as well. Modern humans are thought to have evolved in East Africa.2-4 However there is much debate about the exact nature of their origins, with some researchers suggesting that their origins are closer to South Africa.5 It is thought that the modern humans now living in the Bantu homeland are not direct descendants of our ancient-human ancestors. Scientists think that modern humans emerged from the expansion out of East Africa around 154,000 to 160,000 years ago. Modern humans were clearly present in West Africa by 14,000 years ago,1 but it is possible that they arrived much earlier.

Farming developed in the Bantu homeland region between 4,000 and 2,000 years ago.6,7 Archaeo-logical evidence for agricultural settlements appear around Lake Chad from 1000 BC.8 Lake Chad is a large lake in West Africa surrounded by Chad, Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon. Archaeological evidence from the Nok, - a culture that flourished in Nigeria between 1000 BC and 200 AD9 - tells us that these early agricultural societies developed into larger political groups.

Archaeologists have deduced that the expansion of Bantu people out of West Africa happened as early as 4,000 years ago. This is supported by artifacts linked to early farmers found in the rainfor-ests of Cameroon. It is thought that there were two or more waves of expansion, with the later dis-persal being larger. An expansion closer to 2,000 years ago is linked with the arrival of particular crops including the banana and cereal grains, which enabled population growth. The Bantu people also spread out to search for more agricultural land.10 The evidence for the early use of these farm-ing systems in outlying areas shows that they were similar to methods originating in the Niger-Congo region. Iron smelting developed in the 1st millennium BC11 and iron smelting furnaces are associated with Bantu speaking peoples in these later expansions.12

Bantu people also moved into East Africa, another region with fertile lands for agriculture.13 They moved further south with Bantu people arriving in South Africa by 300 AD.14 The large kingdom of the Zulu people were descendants of these early settlers. They were defeated by the British in the 19th century.15

Many Bantu-speaking areas in West Africa were involved in the slave trade and many African Americans are descended from Bantu people.16 Much of Bantu Africa became subject to European colonial expansion during the time known as the ‘Scramble for Africa'.17

Mitochiondrial DNA studies have found particular changes that distinguish between Khoisan and other sub-Saharan African populations, particularly Southern Bantu and Pygmies.18 Bantu speaking West Africans are distinct from the Khoisan and Afro-Asiatic groups.19 Both Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA studies have found evidence for Bantu expansion both in Southwest and in East Africa.20,21 Studies have shown that African Americans are predominantly related to Niger-Kordofanian Bantu language family speakers that live in the region of present-day Nigeria.22 Future tests may be able to distinguish between different migration events.

References:

1. Allsworth-Jones P. 1987. The earliest human settlement in West Africa and the Sahara. W Afr J Ar-chaeol 17: 87-128.

2. Stringer C. 2003. Human evolution: out of Ethiopia. Nature 423: 692-695.

3. White TD, Asfaw B, DeGusta D, Gilbert H, Richards GD, Suwa G, Howell FC. 2003. Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 423:742-747.

4. McDougall I, Brown FH, Fleagle JG. 2005. Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature 433:733-736.

5. Henn BM, Gignoux CR, Jobin M, Granka JM, Macpherson JM, Kidd JM, Rodríguez-Botigué L, Ra-machandran S, Hon L, Brisbin A, Lin AA, Underhill PA, Comas D, Kidd KK, Norman PJ, Paraham P, Bustamante CD, Mountain JL, Feldman MW. 2011. Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5154.

6. McIntosh SK. 2001. West African Neolithic. In Encyclopedia of prehistory. Springer: USA pp. 323-338.

7. Phillipson DW. 2005. African archaeology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

8. Gronenborn D. 1998. Archaeological and ethnohistorical investigations along the southern fringes of Lake Chad, 1993-1996. Afr Archaeol Rev 15: 225-259.

9. Rupp N, Ameje J, Breunig P. 2005. New studies on the Nok Culture of Central Nigeria. J Afr Ar-chaeol 3: 283-290.

10. Vansina J. 1984. Western Bantu Expansion. J Afr Hist 25: 129-145.

11. Herbert EW. 2003. Red gold of Africa: Copper in precolonial history and culture. Univ of Wisconsin Press: Madison.

12. Childs ST. 1991. Style, technology, and iron smelting furnaces in Bantu-speaking Africa. J Anthropol Archaeol 10: 332-359.

13. Philippson G, Bahuchet S. 1994. Cultivated crops and Bantu migrations in Central and Eastern Afri-ca: a linguistic approach. Azania: Archaeol Res Afr 29: 103-120.

14. Thompson LM. 2001. A History of South Africa. Yale University Press: New Haven.

15. Morris DR. 1994. The Washing of the Spears: A History of the Rise of the Zulu Nation under Shaka and its Fall in the Zulu War of 1879 Vol. 148. Random House: London.

16. Nunn N. 2007. The long-term effects of Africa's slave trades (No. w13367). National Bureau of Economic Research; Harvard.

17. Newman JL. 1997. The peopling of Africa: a Geographic Interpretation. Yale University Press: New Haven.

18. Soodyall H, Vigilant L, Hill AV, Stoneking M, Jenkins T. 1996. mtDNA control-region sequence variation suggests multiple independent origins of an"" Asian-specific"" 9-bp deletion in sub-Saharan Africans. Am J Hum Genet 58: 595-608.

19. Bryc K, Auton A, Nelson MR, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL, Williams S, Froment A, Bodo J-M, Wam-bebe C, Tishkoff SA, Bustamante CD. 2010. Genome-wide patterns of population structure and ad-mixture in West Africans and African Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 786-791.

20. Beleza S, Gusmao L, Amorim A, Carracedo A, Salas A. 2005. The genetic legacy of western Bantu migrations. Hum Genet 117: 366-375.

21. Campbell MC, Tishkoff SA. 2008. African Genetic diversity: Implication for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 9: 403-433.

22. Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, Ehret C, Ranciaro A, Froment A, Hirbo JB, Awomoyi AA, Bodo JM,Doumbo O, Ibrahim M, Juma T, Kotze MJ, Lema G, Moore JH, Mortensen H, Nyambo TB, Omar SA, Powell K, Pretorius JH, Smith MW, Thera MA, Wambebe C, Weber JL, Williams SM. 2009. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science 324: 1035-1044.

/ / / #2 West Africa

West and Central Africa were the main locations that fueled the slave trade that brought substantial numbers

West Africa Story

Africa is regarded as the birthplace of modern humans and its history stretches deep into the past. There is evidence of early human ancestors in West Africa from as early as 2 million years ago, including the early human tool culture known as the Acheulean.2 The transition from earlier human species to modern humans within Africa paints a much more complex picture than the rest of the world, where far fewer migration events are responsible for much of the world's present population.

Studies of mitochondrial DNA revealed that Africans have the highest level of genetic diversity compared with any other region.3,4 There was a complex mosaic of early humans and more modern species within Africa.5 It is thought that modern humans evolved in East Africa6,7 and dispersed across much of the continent, as well as into the rest of the world, either interacting with or completely displacing earlier populations. While it is debatable how much genetic legacy exists from archaic human species in West Africa, it is clear that modern humans moved into the area around 14,000 years ago.2

Farming appeared in West Africa between 4,000 and 2,000 years ago, with dates varying widely depending on the region.8,9 Many of these early farming cultures became rapidly identifiable from archaeological finds. The Nok culture in what is now Nigeria flourished between 1000 BC and 200 AD, producing the earliest evidence for figurative sculptures in Sub-Saharan Africa.10 The decline and disappearance of the Nok remains largely unexplained. Iron-smelting techniques became established in Sub-Saharan Africa by the 1st millennium BC, and copper and iron producing cultures flourished in the 1st millennium AD.11 A tradition based on stone circles known as the Senegambian megaliths appeared around 2,000 years ago and persisted until sometime around 1500 AD. Their function has never been clearly understood in archaeology.12

States on the northern edge of West Africa at the margins of the Sahara, known as the Sahel, began to develop into kingdoms. The most famous of these was the urbanized state that became the Ghana Empire, which existed between 300 AD and 1200 AD.13 The Ghana Empire appeared in the historical records of its Arabic neighbors, with which it traded. The eventual collapse of the Ghana Empire may have been related to invasion by increasingly powerful neighboring kingdoms, though the exact reason has not been established14. Further small kingdoms such as the Sosso, Songhai, and the Mali continued to exist into the following centuries.15

The arrival of Europeans, intent on the capture and enslavement of Africans, coincided with the need for labor in the Americas. Many rulers in the region went to war with their neighbors to supply captives to traders.16 Despite the slave trade being outlawed in the early 19th century, the remainder of the century saw Europeans beginning to formally colonize West Africa. The period of European control disrupted the societies of West Africa that had developed over thousands of years. However, this region has retained much of its distinctiveness and many rich cultures still thrive in the region.

With the science still developing, there are many interesting potential future genetics tests for people that have ancestry from West Africa. Many ancient communities are linked with current ethnic and linguistic groups that are found in the region today. Future testing may be able to determine if an individual has ancestry in any number of these ancient kingdoms. It may also be possible to link ancestry with movement aboard slave ships to the various parts of the Americas.

References:

1. Eltis D. 2000. The rise of African slavery in the Americas. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

2. Allsworth-Jones P. 1987. The earliest human settlement in West Africa and the Sahara. W Afr J Archaeol 17: 87-128.

3. Campbell MC, Tishkoff SA. 2008. African Genetic diversity: Implication for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 9: 403-433.

4. Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, Ehret C, Ranciaro A, Froment A, Hirbo JB, Awomoyi AA, Bodo JM,Doumbo O, Ibrahim M, Juma T, Kotze MJ, Lema G, Moore JH, Mortensen H, Nyambo TB, Omar SA, Powell K, Pretorius JH, Smith MW, Thera MA, Wambebe C, Weber JL, Williams SM. 2009. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science 324: 1035-1044.

5. McBrearty S, Brooks AS. 2000 The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. J Hum Evol 39:453-563.

6. White TD, Asfaw B, DeGusta D, Gilbert H, Richards GD, Suwa G, Howell FC. 2003. Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 423:742-747.

7. McDougall I, Brown FH, Fleagle JG. 2005. Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature 433:733-736.

8. McIntosh SK. 2001. West African Neolithic. In Encyclopedia of prehistory. Springer: USA pp. 323-338.

9. Phillipson DW. 2005. African archaeology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

10. Rupp N, Ameje J, Breunig P. 2005. New studies on the Nok Culture of Central Nigeria. J Afr Archaeol 3: 283-290.

11. Herbert EW. 2003. Red gold of Africa: Copper in precolonial history and culture. University of Wisconsin Press: Madison.

12. Holl A, Bocoum H, Dueppen S, Gallagher D. 2007. Switching mortuary codes and ritual programs: The double-monolith-circle from Sine-Ngayène, Senegal. J Afr Archaeol 5: 127-148.

13. Okpoko AI. 1987. The early urban centres and states of West Africa. W Afr J Archaeol 17: 243-265.

14. Conrad DC, Fisher HJ. 1982, ""The conquest that never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076. I. The external Arabic sources"", History in Africa 9: 21-59

15. Conrad DC. 2009. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. Chelsea House Infobase Publishing: New York.

16. Nunn N. 2007. The long-term effects of Africa's slave trades (No. w13367). National Bureau of Economic Research; Harvard.

/ / / #3 Madagascar

The island of Madagascar has an unusual history. Madagascan people represent a

Madagascar Story

Human settlers arrived surprisingly late to Madagascar. Archaeological evidence (in the form of charcoal remains) points to the earliest human activity dating to around 300 BC,1-3 although the island remained generally uninhabited until around 200 to 500 AD.4,5 This was many thousands of years after humans settled in most other parts of the world. Archaeological discoveries point to dramatic landscape alterations between 100 and 300 AD6-9 and link Madagascar to ancient Indian Ocean trade networks.10

The dominant language of Madagascar today is Malagasy, an Austronesian language closely related to languages found in the Barito River area of Southeastern Borneo.11 Malagasy also has some words from Bantu, Malay, South Sulawesian and Javanese.11,12 There are two main ethnic groups in Madagascar today that share this common language: the Highlanders and the Côtiers.12,13 The Highlanders are more Asian than the coast-dwelling Côtiers, both in appearance and culture, and their main crop is rice. 14

By 1300 AD there was a complex economy involving rice farming, cattle herding, iron smelting and long-distance trade.5 Europeans came into contact with the people of Madagascar from the 1500s, but did not seriously attempt to colonize the region until much later. French and English trading posts were occasionally set up, but there was nothing permanent. During this period, Madagascar developed a feudal system of governance.15 While in contact with Europeans (but not under direct colonial control), Madagascar and its surrounding islands became a famous refuge for pirates and slave traders.16,17 Madagascar became involved with the European slave trade in the 19th century.18 Its monarchy eventually collapsed and the island was invaded by the French. Madagascar gained its independence during the era of decolonization in the middle of the 20th century.

Genetic studies have shown a strong link between Madagascan peoples and Austronesian popula-tions in Southeast Asia. Some mitochondrial DNA haplogroup lineages that link to Polynesian Aus-tronesian groups have been found in Madagascar,19 and this is also true for some Y-chromosome lineages.20 There is also evidence of Bantu genes, which would have come from Africa.21 Future testing may be able give further information on how individuals relate to the original Southeast Asia migrations and African heritage.

References:

1. Gasse F, Van Campo E. 1998. A 40,000-yr pollen and diatom record from Lake Tritrivakely, Mada-gascar, in the southern tropics. Quatern Res 46:299-311.

2. Burney DA, Robinson GS, Burney P. 2003. Sporormiella and the late Holocene extinctions in Mada-gascar. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:10800-10805.

3. Perez VR, Burney DA, Godfrey LR, Nowak-Kemp M. 2003. Butchered sloth lemurs. Evol Anthropol 12:260.

4. Randrianja S, Ellis S. 2009. Madagascar: a short history. Hurst: London.

5. Dewar R, Wright H. 1993. The culture history of Madagascar. J World Prehist 7:417-466.

6. Burney DA. 1987a. Pre-settlement vegetation changes at Lake Tritrivakely, Madagascar. Palaeoecol Africa 18:357-381.

7. Burney DA. 1987b. Late Holocene vegetational change in central Madagascar. Quatern Res 28: 130-143.

8. Burney DA. 1993. Late Holocene environmental changes in arid southwestern Madagascar. Quatern Res 40: 98-106.

9. Matsumoto K, Burney DA. 1994. Late Holocene environments at Lake Mitsinjo, northwestern Mada-gascar. Holocene 4: 16-24.

10. Verlinden C. 1987. The Indian Ocean: The Ancient Period and the Middle Ages. In Chandra, S. (ed.), The Indian Ocean: Explorations in History, Commerce and Politics, Sage, New Delhi, pp. 27-53.

11. Adelaar A. 1995. Asian roots of the Malagasy: a linguistic perspective. Bijdr Taal-Land-V 151:325-356.

12. Blench R. 2007. New palaeo-zoogeographical evidence for the settlement of Madagascar. Azania: J Brit Inst East Africa 42:69-82.

13. Blench R. 2006. The Austronesians in Madagascar and on the East African coast: surveying the linguistic evidence for domestic and translocated animals. Paper presented at: Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics; 2006 January 17-20; Palawan, Philippines. Linguistic So-ciety of the Philippines and SIL International.

14. Tofanelli S, Bertoncini S, Castrì L, Luiselli D, Calafell F, Donati G, Paoli G. 2009. On the origins and admixture of Malagasy: new evidence from high-resolution analyses of paternal and maternal lineages. Mol Biol Evol 26: 2109-2124.

15. Kent RK. 1967. Early kingdoms in Madagascar and the birth of the Sakalava Empire, 1500-1700 (Vol. 1). University of Wisconsin: Madison.

16. Bialuschewski A. 2005. Pirates, slavers, and the indigenous population in Madagascar, c. 1690-1715. Int J Afr Hist Stud 38: 401-425.

17. Kull CA, Tassin J, Moreau S, Ramiarantsoa HR, Blanc-Pamard C, Carrière SM. 2012. The intro-duced flora of Madagascar. Biol Invasion 14: 875-888.

18. Campbell G. 1981. Madagascar and the slave trade, 1810-1895. J Afr Hist 22: 203-227.

19. Razafindrazaka H, Ricaut FX, Cox MP, Mormina M, Dugoujon JM, Randriamarolaza LP, Guitard E, Tonasso L, Ludes B, Crubézy E. 2010. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequences provide new in-sights into the Polynesian motif and the peopling of Madagascar. Eur J Hum Genet 18: 575-581.

20. Chiaroni J, Underhill PA, Cavalli-Sforza LL. 2009. Y chromosome diversity, human expansion, drift, and cultural evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20174-20179.

21. Pierron D, Razafindrazaka H, Pagani L, Ricaut FX, Antao T, Capredon M, Sambo C, Radimilahv C, Rakotoarisoa J-A, Blench RM, Letellier T, Kivisild T. 2014. Genome-wide evidence of Austronesian-Bantu admixture and cultural reversion in a hunter-gatherer group of Madagascar. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 936-941.

DNA MIGRATION ROUTES

* The GPS Origins test is an Autosomal (SNP) test that is not gender specific. Although both Migration Patterns represent your Maternal and Paternal DNA route, we cannot differentiate which route is specifically your parents’ individual route at this time.

GENE POOL %'s

Complete Results

#1 Bantu Africa and the Niger-Congo Areas 33.2%

Origin: Peaks in Nigeria and declines in Senegal, Gambia, and Kenya

#2 West Africa 18.9%

Origin: Peaks in Senegal and Gambia and declines in Algeria and Mororrco

#3 Madagascar 14.9%

Origin: Peaks in Madagascar with residues in South Africa

#4 African Pygmies 8.1%

Origin: Associated with the Pygmy people (Pygmy means short and is assoicated with people) not places.

#5 Nile Valley Peoples 6.7%

Origin: Peaks in Western Ethiopia and south Sudan

#6 Northwestern Africa 6.3%

Origin: Peaks in Algeria and declines in Morocco and Tunisia

#7 Tuva 5.3%

Origin: Peaks in south Siberia (Russians: Tuvinian) and declines in North Mongolia

#8 Western Siberia 3.5%

Origin: Peaks in Krasnoyarsk Krai and declines towards east Russia

#9 Northern Mongolia and Eastern Siberia 2%

Origin: Peaks in North Mongolia and declines in Siberia

#10 Southern Ethiopia 1.1%

Origin: Localized to South Ethiopia

Human Origins : Our Shared History to Your Story

The questions of who we are and where we come from have been asked for throughout our history. Once we explained our origins with mythology and folklore but now we utilize modern science to answer them.

Genetics help us tell the story of our origins from the beginning, through the formation of the human gene pools and to the last 2000 years of history.

The test results you have just received, along with the following information, will help you understand your personal story, from the shared history of all humans to your unique family story.

From Sea to Land: Our Shared History

Our origins lie far beyond the first appearance of humans, with an evolutionary story common to many forms of life on earth. About 360 million years ago fish-like creatures ventured out of the Devonian Sea and became the first reptiles. After hundreds of millions years of evolution the mammals emerged after the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago thrust them into the evolutionary spotlight, and allowed them to expand into the world the dinosaurs left vacant.

Our human story really begins with the origin of primates, which split away from the other mammalian groups between 65 and 80 million years ago. It would be at least another 60 million years before the appearance of the species Ardipithecus, an ape that evolved from the Old World Monkeys and is regarded as the first fossil human ancestor.

Fossil finds from Ardipithecus in Ethiopia date it to between 4 and 6 million years ago.12 This species could walk on two legs like humans but shared other characteristics with chimpanzees. Ardipithecus further developed into a number of lineages found throughout East Africa and South Africa that are known as the Australopithecines.13

Over the next 3 million years, many Australopithecine species appeared in Africa but they evolved little; their brains remained roughly the same size as those of chimpanzees and they did not use tools. Around 3 million years ago, the subspecies Homo habilis14 began using stone tools, and by 1.5 million years ago the fire-mastering Homo erectus appeared. Fossils reveal that Homo erectus had a much bigger brain than its Australopithecine ancestors. This subspecies began spreading across much of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, while the Australopithecines began to disappear.15

Next, a new human subspecies, the Neanderthals, appeared. They evolved from a Homo erectus relative outside of Africa and had spread widely throughout Europe and the Middle East 500,000 years ago.16 Neanderthals had stocky builds and thick limbs and were specially adapted to the Ice Age conditions. There is evidence that Neanderthals buried their dead, a practice once thought exclusive to modern humans,17,18 which raises questions about the nature of the Neanderthal’s genetic contribution to modern humans.19

Africa: The First Modern Humans

It is thought that the ancestor of modern humans is one of the Homo erectus relatives, which appeared in East Africa sometime between 100,000 to 200,000 years ago.

Many different ancient human species also evolved outside Africa, and persisted for more than a million years of geologic time. Their fossils have been unearthed in Europe, Southeast Asia, and China. Yet this diversity had all but disappeared by 100,000 years ago, and human fossils became remarkably uniform across the globe.23

The theory that has become known as the Out of Africa model began with a study in the late 1980s, investigating small changes in the DNA carried by the mitochondria - the DNA passed down by the mother.24 The study analyzed DNA changes in the mitochondrial genome, and surmised that all humans diverged from a single ancestor living 200,000 years ago in Africa. While this does not indicate that there was just one mother, or ‘African Eve’, for all humanity, the results suggested that all humans alive today descended from a single population residing in Africa more recently than any of the previously mentioned early human species.

The Out of Africa model has also been applied to research on the Y chromosome.25,26 This chromosome is found only in male lineages and passed down through the generations, unchanged for the most part. A recent study estimates that the ‘African Adam’ lived 208,000 years ago27.

Beyond Africa: Colonizing the Continents

Mitochondrial and Y chromosomal DNA have been our primary tools for deciphering the human story because each person receives only one copy from each parent. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down from the mother and Y chromosomal DNA from the father, allowing scientists to track the ancestry of both the maternal and paternal lines. Perhaps one of the most interesting stories told by the mitochondrial and Y chromosomal DNA is how humans colonized the world.

The earliest human migrants appear to have reached Southern China some 80,000 years ago28, and DNA studies suggest they may have interbred with Neanderthals on their way through the Middle East.29 They then spread to the rest of Asia along a route that probably tracks south of the Himalayas and into East Asia between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago,30 possibly interbreeding with another subspecies known as the Denisovians.31

Archaeological and genetic evidence indicate that modern humans crossed the ocean from Southeast Asia and reached the islands near the tropical Pacific area of Oceania as far back as 50,000 years ago, probably in small water craft.32 At the same time, populations spread to Europe through Turkey and into Central Asia. Some of these Central Asian migrants subsequently moved westward from the Ural Mountains and may be represented today by the peoples of Northern Europe and of the Baltic region, such as the Sami people.

Climate and geography delayed further migrations of modern humans into other areas of the world. Much of northern Eurasia was extremely cold during the last Ice Age (11,000 to 12,000 years ago) and human populations remained small and isolated. A small group of people from Siberia, however, managed to reach North America around 18,000 years ago33 by way of a land bridge that existed when sea levels were lower. They moved south, and by 15,000 years ago, began to populate South America.

There were several more migratory waves to the Americas with the most recent being the Inuit, who colonized the Arctic of North America between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago.

Asian migration also continued eastwards to Oceania. The large islands of Oceania that are closest to Asia have been inhabited for at least 30,000 years, while the most isolated islands of Northeastern Oceania remained uninhabited until just 3,500 years ago.34,35 The people who made the first voyages into this region were Austronesians, a group that emigrated from an area around present day Taiwan and are today known as Polynesians.

But as the last Ice Age came to an end and the climate warmed, a human cultural revolution was about to start, and it began in the Middle East.

Agriculture and the Growth of Civilization

The transition from hunter-gathering to farming occurred in the Middle East between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago,36 and between 9,000 and 10,000 years ago in China37 and parts of the Americas.38,39 By 5,000 years ago agriculture had facilitated the rise of some of the first large civilizations such as Mesopotamia in West Asia,40 the Maya in Central America,41 and the earliest Chinese civilizations along the Yangtze.42

Early farming cultures then expanded into new areas. Farmers from the Middle East brought agriculture to Europe and rice farming travelled with groups across East Asia. This expansion was accompanied by a genetic reshuffling as different groups came into contact and reproduced. Such reshuffling has been a continuous process over the last 10,000 years.

Genetic research has played a key role in understanding the migrations that took place during this period. Mitochondrial DNA lineages have been used to confirm and enhance archaeological interpretations such as tracing the ancestry of Norse and Gaelic populations, and Y chromosomal studies have been used to track male lineages in studies of Oceania.

Genetic Origins (Gene Pools): The Key to Identifying Your Ancestral Communities

As humans traversed the globe and colonized different continents each group accumulated small differences in their DNA. Most of these differences or mutations occurred in the X chromosome and autosomal chromosomes that are inherited from both parents and allows us to follow the specific journeys made by each human group.

Some genetic roads diverged, not meeting again until modern times, while others led back to one another as genetically distinct groups. The accumulations of mutations in people from different areas of the world are what allow us today to distinguish different groups from one another.

DNA mutations may have been enhanced by the custom of marrying within an tribe, class, or social group, creating a group of people who were more similar to one another genetically than they were to their ancestors and neighboring groups - in other words, creating a new gene pool or genetic origin..

It is difficult to know exactly how many gene pools there are because every geneltic origin includes “gene puddles” where small, isolated groups of people married only within their local group, acquiring and maintaining unique mutations over time. At this time, scientists have identified about forty gene pools from all over the world. Over time, some of these gene pools spilled toward? each other, particularly those in Eurasia, whereas other pools remained more constant.

Recent History and the Genetic Melting Pot

As ancient peoples traded, conquered, enslaved and fell in love, they spread their genes, along with their unique mutations, across larger areas at an increasingly rapid pace, interweaving previously distinct parts of the original gene pools. If, in the past, human groups diverged from one another and became genetically distinct, recent history has been characterized by populations coming together creating new genetic tapestries out of the original genetic origin. Today, every one of us is the product of these historical genetic exchanges: it is extremely rare to find individuals whose DNA belongs to a single gene pool.

Because the X and autosomal chromosomes contain the accumulated mutations that correspond with different gene pools, they provides a more nuanced picture of historical interactions in the past. Your genetic origin results will show you how your genome is linked to the human story of the populations who lived 60,000-15,000 years ago.

Empires, Pandemic and More Migration: Your Story in the Modern World

The past 2,000 years of human history have seen the rise and fall of empires that spanned entire continents, such as the Persian, Roman, Mongol, Arab Caliphate and most recently, the British Empire.

The expansion of European empires brought European DNA to many different parts of the world such as Australia, Asia and particularly the Americas, where the intermingling of Europeans and native tribes has led to many central and south Americans having mixed ancestry.

Pandemics, such as the Black Death in Europe and smallpox in the Americas caused widespread devastation. Conquests by Viking raiders reshaped entire cultures and identities. All of these events have left their mark in the DNA of present-day populations.

Countries such as the United States, which have experienced large waves of migration from different areas in the last two hundred years have facilitated the further mixing of many different gene pools.

Between the 17th and 19th centuries the slave trade brought up to 650,000 Africans to the United States. They were joined by 4.5 million Irish people who escaped famine and poverty between 1820 and 1930, Other groups to enter the United States between the mid-19th and early 20th centuries include about 5 million Germans, over 2 million European jews, 4 million Italians and up to 300,000 Chinese.

Consequently, these migrations merged gene pools that had, thus far, remained largely separate due to geographical barriers. Many Americans and British now share genetic origins with up to a dozen different gene pools, some of which have diverged more than 60,000 years ago, such as the European and Native American gene pools.

Your GPS Origins results reveal your genetic origins and the journey your DNA has made with end-points recorded each time the DNA has markedly changed through intermarriages.

For example, if you have Scottish ancestry your results could show that you are descended from the Viking ancestors who arrived in the Medieval era, but did not mix with Scots and retained their Danish origin. If you are African American, you may learn about connections to the Bantu peoples and the pre-colonial trading kingdoms in West Africa. If you are an Ashkenazic Jew, GPS Origins may trace your origin to the ancient Ashkenaz in northeastern Turkey.

Ongoing genetic research of archaeological remains could mean that, in the future, you may be able to match your background with a range of individuals - whether that is an ancient Mayan King found in a temple complex in Guatemala, a warrior from a Viking boat burial or a flint-knapping craftsman from Mesolithic Germany. The human story, as told through our genes, is only beginning.

Now, you are ready to see your results.

Out of Africa Story References:

1. Nielsen PE, Engholm M, Berg RH, Buchardt O. 1991. Science 254: 1497–1500.

2. Mintmire JW, Dunlap BI. White CT. 1992. Phys Rev Lett 68: 631–634.

3. Zhu M, Ahlberg PE, Zhao W, Jia L. 2002. Palaeontology: First Devonian tetrapod from Asia. Nature 420: 760-761.

4. Rose KD. 1994. The earliest primates. Evol Anthropol 3: 159-173.

5. Clemens WA. 2004. Purgatorius (Plesiadapiformes, Primates?, Mammalia), a Paleocene immigrant into northeastern Montana: stratigraphic occurrences and incisor proportions. Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History: 36: 3-13.

6. Rose KD, Godinot M, Bown TM. 1994. The early radiation of Euprimates and the initial diversification of Omomyidae. In Fleagle JG, Kay RF. Eds. Anthropoid origins. Springer: United States. pp. 1-28.

7. Bajpai S, Kay RF, Williams BA, Das DP, Kapur VV, Tiwari BN. 2008. The oldest Asian record of Anthropoidea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 11093-11098.

8. Zalmout IS, Sanders WJ, MacLatchy LM, Gunnell GF, Al-Mufarreh YA, Ali MA, Nasser AH, Al-Masari AM, Al-Sobhi SA, Nadhra AO, Matari AH, Wilson JA, Gingerich PD. 2010. New Oligocene primate from Saudi Arabia and the divergence of apes and Old World monkeys. Nature 466: 360-364.

9. Patterson N, Richter DJ, Gnerre S, Lander ES, Reich D. 2006. Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees. Nature 441: 1103-1108.

10. Langergraber KE, Prüfer K, Rowney C, Boesch C, Crockford C, Fawcett K, Inoue-Muruyama M, Mitano JC, Muller MN, Robbins MM, Schubert G, Stoinski TS, Viola B, Watts D, Wittig RM, Wrangham RW, Zuberbühler K, Pääbo S, Vigilant L. 2012. Generation times in wild chimpanzees and gorillas suggest earlier divergence times in great ape and human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 15716-15721.

11. Guy F, Lieberman DE, Pilbeam D, de León MP, Likius A, Mackaye HT, Vignaud P, Zollikofer C, Brunet M. 2005. Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 18836-18841.

12. White TD, Asfaw B, Beyene Y, Haile-Selassie Y, Lovejoy CO, Suwa G, WoldeGabriel G. 2009. Ardipithecus ramidus and the paleobiology of early hominids. Science 326: 64-86.

13. Reed KE. 1997. Early hominid evolution and ecological change through the African Plio-Pleistocene. J Hum Evol 32: 289-322.

14. Ungar PS, Grine FE, Teaford MF. 2006. Diet in early Homo: a review of the evidence and a new model of adaptive versatility. Ann Rev Anthropol 35: 209-228.

15. Antón SC. 2003. Natural history of Homo erectus. Am J Phys Anthropol 122(S37): 126-170.

16. de Castro JMB, Martinón-Torres M, Gómez-Robles A, Margvelashvili A, Arsuaga JL, Carretero JM, Martinex I, Sarmiento S. 2011. The Gran Dolina-TD6 human fossil remains and the origin of Neanderthals. In Condemi S, Weniger GC. Eds. Continuity and discontinuity in the peopling of Europe. Springer: Netherlands. pp. 67-75.

17. Pettitt P. 2002. The Neanderthal dead: exploring mortuary variability in Middle Palaeolithic Eurasia. Before Farming (1): 1-26.

18. Zilhao J. 2012. Personal ornaments and symbolism among the Neanderthals. Developments in Quaternary Science 16: 35-49.

19. Lowery RK, Uribe G, Jimenez EB, Weiss MA, Herrera KJ, Regueiro M, Herrera RJ. 2013. Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: Introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms. Gene 530: 83-94.

20. Stringer C. 2003. Human evolution: out of Ethiopia. Nature 423: 692-695.

21. White TD, Asfaw B, DeGusta D, Gilbert H, Richards GD, Suwa G, Howell FC. 2003. Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 423: 742-747.

22. Gunz P, Bookstein FL, Mitteroecker P, Stadlmayr A, Seidler H, Weber GW. 2009. Early modern human diversity suggests subdivided population structure and a complex out-of-Africa scenario. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6094-6098.

23. Templeton A. 2002. Out of Africa again and again. Nature 416: 45-51.

24. Cann RL, Rickards O, Lum JK. 1994. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution: Our one lucky mother. In Nitecki MH, Nitecki DV eds. Origins of anatomically modern humans. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Springer: United States. pp. 135-148.

25. Underhill PA, Shen P, Lin AA, Jin L, Passarino G, Yang WH, Kauffman E, Bonné-Tamir B, Bertranpetit J, Francalacci P, Ibrahum M, Jenkins T, Kidd JR, Mehdi SQ, Seielstad MT, Wells RS, Piazza A, Davis RW, Feldman MW, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Oefner PJ. 2000. Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations. Nature genet 26: 358-361.

26. Underhill PA, Passarino G, Lin AA, Shen P, Mirazon Lahr M, Foley RA, Oefner PJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL. 2001. The phylogeography of Y chromosome binary haplotypes and the origins of modern human populations. Ann Hum Genet 65: 43-62.

27. Elhaik E, Tatarinova TV, Klyosov AA, Graur D. 2014. The ‘extremely ancient’chromosome that isn’t: a forensic bioinformatic investigation of Albert Perry’s X-degenerate portion of the Y chromosome. Eur J Hum Genet 22: 1111-1116.

28. Dennell R. 2015. Palaeoanthropology: Homo sapiens in China 80,000 years ago. Nature 526: 647-648.

29. Sankararaman S, Patterson N, Li H, Pääbo S, Reich D. 2012. The date of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans. PLOS Genetics OI: 10.1371:1002947.

30. Armitage SJ, Jasim SA, Marks AE, Parker AG, Usik VI, Uerpmann HP. 2011. The southern route “Out of Africa”: evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia. Science 331: 453-456.

31. Gibbons A. 2011. Who were the Denisovans?. Science 333: 1084-1087.

32. Mellars P. 2006. Going east: new genetic and archaeological perspectives on the modern human colonization of Eurasia. Science 313: 796-800.

33. Meltzer DJ. 2009. First peoples in a new world: colonizing ice age America. Univ of California Press: Berkeley.

34. Bellwood P. 1985. Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago. University of Hawai’i Press; Honolulu.

35. Kirch PV. 2000. On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact. University of California Press: Berkeley.

36. Brown TA, Jones MK, Powell W, Allaby RG. 2009. The complex origins of domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24: 103-109.

37. Zhao Z. 2011. New archaeobotanic data for the study of the origins of agriculture in China. Current Anthropology 52(S4): S295-S306.

38. Smith BD. 1994. The origins of agriculture in the Americas. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 3: 174-184.

39. Smith BD. 1997. The initial domestication of Cucurbita pepo in the Americas 10,000 years ago. Science 276: 932-934.

40. Postgate JN. 1992. Early Mesopotamia. Society and Economy at the Dawn of History, 52: 92-95.

41. Demarest A. 2004. Ancient Maya: The rise and fall of a rainforest civilization (Vol. 3). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

42. Yasuda Y, Fujiki T, Nasu H, Kato M, Morita Y, Mori Y, Kanehara M, Toyama S, Yano A, Okuno M, Jiejun H, Ishihara S, Kitagawa H, Fukusawa H, Narus T. 2004. Environmental archaeology at the Chengtoushan site, Hunan Province, China, and implications for environmental change and the rise and fall of the Yangtze River civilization. Quatern Int 123: 149-158.

43. Helgason A, Hickey E, Goodacre S, Bosnes V, Stefánsson K, Ward R, Sykes B. 2001. mtDNA and the islands of the North Atlantic: estimating the proportions of Norse and Gaelic ancestry. Am J Hum Genet 68: 723-737.

44. Kayser M, Choi Y, van Oven M, Mona S, Brauer S, Trent RJ, Suarkia D, Schiefenhövel W, Stoneking M. 2008. The impact of the Austronesian expansion: evidence from mtDNA and Y chromosome diversity in the Admiralty Islands of Melanesia. Mol Biol Evol 25: 1362-1374.

45. Herlihy D, Cohn SK. 1997. The Black Death and the transformation of the West. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

46. Patterson KB, Runge T. 2002. Smallpox and the Native American. Am J Med Sci 323: 216-222.